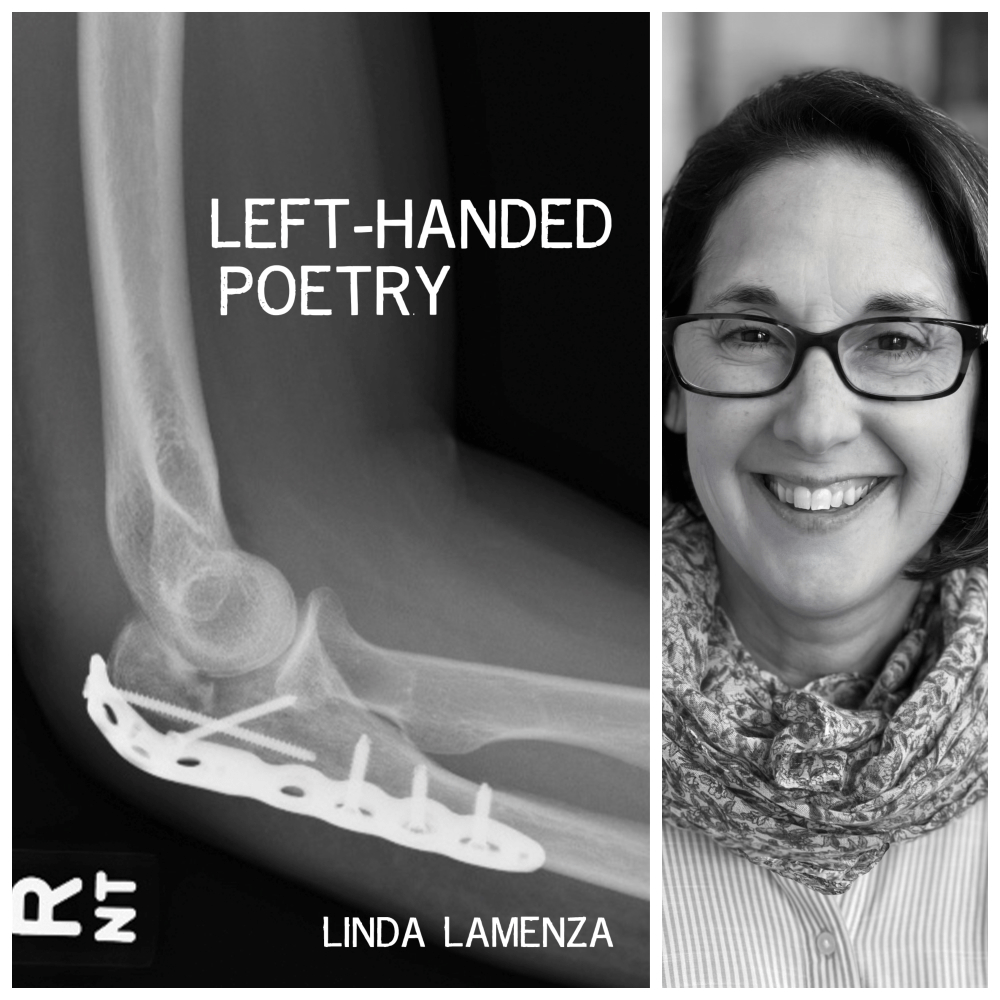

Left-Handed Poetry, Linda Lamenza, Finishing Line Press, 2024, 44 pages, 17.99

Reviewed by Jennifer Martelli

In her poem, “A Month in the Rehab Unit,” Linda Lamenza writes

I am shattered

into no particular

order like bits of colored glass

on the stone floor.

Left-Handed Poetry, Lamenza’s latest collection, is an account of a brutal car accident that left the speaker with a broken body, broken plans, “waiting for anyone to tell me / who I am.” The poems engage with trauma and pain by showing how our temporal and physical boundaries break as easily as bone. The speaker in “Oxy,” a direct address to the narcotic, confronts the power of pain and of pain-killers,

All my plans, broken.

Weren’t we going to Italy?

Didn’t I weep to please you?

Most of us have been involved in some type of car accident—whether a fender-bender or serious collision—and can understand this sense of wanting to go back in time, to just before the impact. Lamenza masterfully navigates this time-shifting, this regret of the breaking. “Right of Way,” a poem broken down the middle, offers the wish

If I could

do it over,

I would

avoid it,

the scene,

the 6-car lot

at the Mobil Station

(Dunkin’ Donuts inside).

As I read, I thought of Jane Kenyon’s poem, “Otherwise,” where the speaker contemplates a different reality in the face of mortality, “At noon I lay down / with my mate. I might / have been otherwise.” Pain—and other assaults—can breed an obsession with past or present. Life, with all its monotonies, is easily shattered. In her title poem, “Left-Handed Poetry,” Lamenza grapples with this relearning of a simple tasks,

I create a plan

for the first day of school,

though I won’t be teaching.

I pretend to go

see the new Mission

Impossible movie . . .

After trauma, the body becomes something more (or less) than what it was: left-handed when it was right-handed, awkward, limited, dependent, a cyborg. After the impact in “Honda Pilot,” the speaker is

. . . part of her

SUV,

my DNA

forever embedded

in her bumper.

Lamenza’s prowess as a poet (even a left-handed one) can be seen in her descriptions of this fusion. Describing her new body parts in “Atomic Number 22: Titanium,” she writes

Found in the meteorites and the sun,

only element that burns in pure

nitrogen . . .

//

artists’ paints, my

reconstructed elbow.

The poet fuses places as well. Whether due to pain, grief, or pain killers, Italy merges with the hospital room in “On The Asphalt,”

From my mind I draw a card: Courage,

cross the Ponte Vecchio,

toss in the Arno my pain.

The witnesses to this accident at the Mobil Station become

tourists in the Uffizi courtyard

who pose next to the twin

of Michelangelo’s David.

Both of us passing for real.

Like the patient in Plath’s “Tulips,” who watches the red blooms in her hospital room and yearns for “a country as far away as health,” the speaker’s pain is transformed into a study of color, of

luminosity trapped

inside the rain,

twice reflected,

reversing order:

Violet Indigo

Blue Green

Yellow Orange

Red—

The scars and damage on the body take on the hues of “Monet’s Water Lilies / in deep reds and pinks.” Lamenza writes in “Diagnosis Wrecked,” that the damage is “a ghoulish work of art / by Saturday’s driver.”

Linda Lamenza expresses masterfully the power that pain has to transform lives, colors, places, time. “Truth is the purple swollen / disaster of my foot,” Lamenza tell us. The poems in Left-Handed Poet embrace the unreliability of life, this place “somewhere / between earth and sky,” as well as the fragility and strength of the body and of the family. Linda Lamenza’s gaze is unflinching, and her voice, insistent. “Let my selves / come together” the speaker commands, “in stained beauty / shimmer in sunlight.”

ECHOES OF GROWING UP ITALIAN: Women’s Stories from Across North America, edited by Gina Valle, Foreword by Elizabeth Renzetti, Guernica Editions, 2024, 200 pages, $18.00

“But they grew up in the same family,” is an oft-heard refrain from people baffled by discordant differences in the personalities and/or behaviors of a set of siblings. Psychologists propose that siblings are born into, and grow up within, different families. Totally different families. That every sibling has a different set of the same parents, based on that child’s birth order, their parents’ ages and life experience at the time, and their parents’ child raising experience.

ECHOES of Growing Up Italian, Women’s Stories from Across North America, is a family story, a fascinating anthology written by fifteen North American female authors who grew up in a broader family – the Italian diaspora family. This collection of fiction and nonfiction stories and essays come from children of emigrants, or transplants themselves, who departed their tiny, native Italy to find new lives and opportunity in the vast expanse of Canada. Their tales are evidence that although these writers’ families left Italy, Italy has never left them, even into the second generation removed from their nation of birth. Italy and all things Italian flow through their veins, regardless of whether “the old country” and its customs resonate with these new North Americans or not.

Their stories were born in Sicily, Rome, Calabria, Milan, the tales are peppered with dialects differing from north to south, yet each story down the length of the boot resonated. I nodded, I smiled, I cried, I laughed out loud, and I recognized my immigrant Italian families in every single one. At times the echoes of Italy in these writings are whispers, at times they are shouts, each one reverberating with a different sound: the lapping waves of an ocean voyage, the soaring music of an opera or of a wedding tarantella, the hushed incantations to banish malocchio, the superstitions only whispered, the warnings to adhere to the old ways, the admonitions to obey, to respect, and the retorts from the resistant – and sometimes brazen – new Canadian Americans caught in a tug-of-war between The Old and The New.

Forging a new path, either by their choice or that of their parents, the protagonists in this collection of stories are young women intent on shedding enough of the old to fit in, to maintain la bella figura, while navigating a new language, both the spoken one and the unspoken one resounding in their adoption of current styles and new customs, often to dismay and discord within their homes.

I was not raised in any of the families whose story/songs fill the pages of this anthology/album, but these fifteen female Italian-North American writers are my siblings. Their stories ring true. In my heart and in my head, I recognized all the melodies, and I knew every lyric.