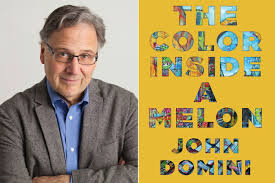

The Color Inside a Melon by John Domini

Review and Interview by Mark Spano

Naples is a mean, dirty town, probably one of the toughest places in Europe. John Domini’s new book, The Color Inside the Melon is a crime story set in the immigrant demimonde of present-day Naples. Called the City of the Sun, Naples is earth-quake prone, crowded next to a volcano, crammed with five hundred churches, congested with a cacophony of vehicles, and is also teeming with nearly a million lives lived in the shadows.

Domini’s book is more “più nero” (the blackest) than merely “noir.” The reader is following a main character who has taken on the challenge to find out who killed a friend in a place where survival is challenge enough. Risto, an African is from Mogadishu Somalia, and is plagued by flashbacks from having witnessed his younger brother’s decapitation. Despite his numerous and extraordinary adversities, he has, with the support of his Neapolitan wife, made a life for himself as an art dealer in Naples. Theirs is a netherworld of polymorphous sex and frequent and often random violence.

Risto is an art dealer, trading in photography of the harshest images in the lives of those immigrants struggling to survive in Naples. These photos are intricately articulated horrors. The beauty that reigned so long in Italian art no longer reigns in the art of modern-day Naples. Risto’s art, like his quest to resolve and understand the murder of his friend, is both a dark and ugly pursuit.

With such a story, as a reviewer, I feel obliged caution the prospective reader while not spoiling the plot. I must state flatly that The Color Inside the Melon, is not your tried and true Graham Greene novel of foreign intrigue or your take-to-the beach Agatha Christie murder mystery. It is not solely the hardscrabble setting and characters that might affront the faint of heart. We are led through the book by a third person narrator whose prose voice can be as bizarre as the fictional voices of Anthony Burgess or William S. Burroughs or the poetic voices of John Ashbery or Frank O’Hara.

This is not an easy book. At times, I found it hard to read as it offered up realities that were hard to swallow, in a style offering allusions current to the moment, global in scope, that are everywhere throughout the text. Domini refers to these allusions as “associative leaps.” Often because of these leaps, there were times, while reading the book, I shouted out-loud, “Where did that come from?”

I recently sat down with John Domini to talk about his new book The Color Inside the Melon.

MARK SPANO: John, it seems to me a crime novel must balance the elements of grit of character, place, and the elegance of storytelling.

JOHN DOMINI: As you know, Mark, this novel is the closer, a finale of a loose trilogy. All three books are set in Naples after the next earthquake. Everyone in Naples understands it’s going to happen sometime. The last big earthquake was in 1980. The tectonics around there are unstable with volcanos either side. I found it a fascinating city, a city both of eternal stasis and constant change, a paradox by the Tyrrhenian Sea. I wanted to write about the whole city, not the usual thing of an American’s adventure in Italy. So, I had to write in other points of view than mine.

If you’re working like that—a social portrait—if you’re thinking in those terms, a portrait of the moment, and the one that gets out from behind the protection of American power, pretty soon you’re running into elements of a crime novel. I’m not the only guy. Tolstoy in his social portraits had a lot of crimes involved. This particular one is from the point of view of an African immigrant, the people who are changing Naples as if in another sort of earthquake. This particular one suggested a very common crime all across Italy nowadays, the murder of a clandestino ,the murder of an unregistered immigrant, an illegal immigrant, and what the police do and usually don’t do about it. Such a crime seemed to fit what I was interested in working with.

Then, it became important that it be a good and interesting crime, that there be levels that wouldn’t occur to somebody at first glance.

Raymond Chandler has a small list of rules for the mystery. Any crime story must be such that it eludes a reasonably intelligent reader. He also says that it can’t depend on some impossible complex setup that could never happen in the real world. That’s why Chandler hated Agatha Christie, and why he would have hated Dan Brown too. And on top of that, it was very important for me to avoid the “idiot plot.” The plot that works only if everyone involved is an idiot.

For someone to succeed as my main character Risto has succeeded—as a refugee—is a very tough thing to do. He’s got to be smart.

MS: He’s a cut above.

JD: Yes, and Risto is yet another example of someone from a marginal population succeeding in the arts. Where did African-Americans first make their mark? If it wasn’t in sports, it was in the arts. The arts is the closest thing to a meritocracy that we have.

MS: You mentioned earlier, “the protection of American power,” does that facade somehow veil the real place from the American visitor? Can you talk about that?

JD: Arguably, American cultural dominance is even more of a force than its army. It applies to this novel because it’s very important that Risto and the people around him are aware of all these layers of status. Despite his remarkable accomplishments, Risto has never entirely escaped. He is reminded that he is below a Neapolitan policeman who is below a Roman policeman who is below an American attaché to the American embassy. Also, just among the so called “white Italians,” there’s a whole pecking order. Risto actually says to his wife, “They’re all in some song, all the old stories…It’s a city that gets older but never gets anywhere. Everybody stays in the piazza. Everybody sits by the fire telling the old stories. And they say Africans are tribal.”

To put it another way, Italy must be understood as a conservative country. The whole point of Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, and Sorentino’s remake of La Dolce Vita is that the country really doesn’t know what to do with its edgier, freakier, less traditional manifestations. Even now there is no legal recourse for homosexual couples. As difficult as it is in the U.S., it is more difficult in Italy.

Knowing who’s an American and what they can and can’t do in Italy is a reflection of these very carefully defined strata of power, still very clear in Italy, and still exerting serious social force. Having made it in Naples, which is what Risto has done, is less than having made it in the North. This is a reflection of a society that is still struggling to enter into the late Twentieth Century let alone the Twenty-First.

MS: The variety of reference, allusion, argot in the voice of narrator, I am assuming is a voice of that environment of the Naples demimonde. This voice throws everything, including the kitchen sink, at the wall. While reading I said to myself very few people write like this, and very few people write like this and hang the term “prose” on it. This is prose fiction, but it is prose fiction with a very poetic approach. Tell me if I’m wrong but I believe you are greatly influenced by some modern poets.

JD: It is very important to me to have a style that is interesting and alive in itself. You’re constantly trying to forge new ways, more vital ways to say something. That was one of the great accomplishments of the New York school, Ginsberg, Frank O’Hara, and others.

I do have prose people in mind when I’m writing. Italo Calvino, whether in Italian or in a great translation by William Weaver, is an extraordinary style. I’m not sure of the name Donald Barthelme means anything to you, but I had in mind his amazingly quick wit and his ability to make an associative leap that nonetheless landed you right where you needed to.

Bio:

Mark Spano, writer and filmmaker, has over 30 years of experience in film and television production, the performing arts, and arts management. His feature documentary “Sicily: Land of Love and Strife” premiered in April of 2018. He is also is a contributing editor for the online magazine Times of Sicily. Mark’s novel entitled Midland Club, was recently published by Thunderfoot Press. Midland Club has received two awards and significant critical acclaim. He is presently developingMidland Club for the screen. He holds an MBA from Marymount University and an MA from American University. He also holds dual US/Italian citizenship.

MS: I like the term “associative leap,” because your associative leaps are often startling.

JD: Some of that, of course, is the demimonde. It’s the way that people in the arts, people in performance talk about things. They’ll make odd connections.

MS: There’s something ironic about this story, in that our forefathers were trying to get out of Naples for the promised land. And, here’s this African who views Naples as the promised land.

JD: There’s been a great deal written about this in the Italian press. They talk about all of Italy, but it’s primarily southern Italy. That Italy has gone from a place you emigrate from to a place you immigrate to. You understand that to an African who has crossed safely—you understand that many of them have connection in Europe already—they make the crossing safe, they pay off all the bribes they have to pay and then they connect with their clansman or cousin or something. They have some idea of what they’re getting into, I mean, and so if someone said to them that you are part of some remarkable irony of our time, they couldn’t care less.

The novelist, however needs to be aware of the larger ironies, the larger shifts in the society. A good social novelist needs to be aware that. His job (or hers) is to find vital and dramatic ways to express it.

MS: And, your book is doing that in the present moment and in the present moment, things are very grave, indeed, in Southern Italy.

JD: It’s another book that will explain that government in southern Italy is essentially criminal. If you want to get anything done you have to work with the Camorra.

MS: My observations in Sicily have been that if I know what’s going on, Rome knows what’s going on. And, if Rome knows it, they know it at The Hague, and all the way up the line.

JD: This is Roberto Saviano’s argument in Gomorrah. The police are doing the best they can. The Neapolitans I know best, my family, believe that the police are doing the best they can. It’s the power at the top that checks the police. They want the votes that the Camorra can line up, and they won’t break the power of the Camorra.

It is important in my book that Risto is not a member of the police, that he is not a professional detective. The answer’s complex, to be sure, it occupies the entire text, but fundamentally this man is in the grip of the very empathy my novel is trying to create. He knows the victim could be him—a young man with big dreams.