Assassins Against the Old Order:

Italian Anarchist Violence in Fin de Siècle Europe

Nunzio Pernicone and Fraser M. Ottanelli

University of Illinois Press

REVIEWED BY GEORGE DE STEFANO

Anarchists long have been stereotyped as “bomb throwers,” who prefer to blow up representatives of oppressive governments, rather than build mass movements and political parties. Some anarchists fit this profile, but those who historically have favored or engaged in “propaganda of the deed”—individual acts of violence intended to spark revolutionary change—have been poorly understood. Often, they are maligned as fanatics, criminals, and mentally ill.

Assassins Against the Old Order offers a valuable corrective to this skewed image. Although there exists a substantial literature on Italian anarchism, no previous book has focused on the topic of political assassination as a revolutionary tactic of Italian anarchists. Based on original research, the book, co-authored by the late Nunzio Pernicone and Fraser M. Ottanelli, fills a gap in the historiography of the Italian left.

As Ottanelli writes in the preface, it is the product of an “unlikely friendship” between its primary author, Pernicone, and Ottanelli. Ottanelli edited Pernicone’s draft chapters, wrote the preface, the introduction, and the conclusion, and updated the bibliography. “Unlikely” because the authors, both academic historians, represent two different and often conflicting radical traditions; Marxism, in Ottanelli’s case, and anarchism, for Pernicone. Despite their differences, they found common ground and, as Ottanelli says, they often were on the same side of issues. With trust established, as well as friendship, in 2013, Pernicone, then dying from cancer, asked Ottanelli to finish the book. Assassins Against the Old Order is, then, a significant historical study and a tribute to an eminent scholar.

Ottanelli notes that “Italian anarchists did indeed compile a formidable record” in political assassination—those killed in “attentats” include President Sadi Carnot of France (1894); Spanish prime minister Antonio Cànovas del Castillo in 1897; Austrian Empress Elizabeth (1898); and King Umberto I of Italy (1900). Their assassins respectively were Sante Caserio, Michele Angiolillo, Luigi Lucheni, and Gaetano Bresci. Pietro Acciarito failed in his 1897 attempt to assassinate Umberto; Paolo Lega failed to kill Italian prime minister Francesco Crispi in 1894.

To elucidate the particularities of Italian anarchist violence, the book focuses on:

…the intricate connection between the revolutionary traditions of the Risorgimento [Italian unification] with Italian anarchist violence in the 1890s; the role of the Russian anarchist revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin; the anarchist insurrections in southern Italy of the 1870s; the suppression of the First International [The International Workingmen’s Association, established in 1864] in Italy and the resulting transformation in the ideology and structure of the movement; the changing and diverse attitudes toward political violence that resulted from this transformation as expressed by the movement’s principal theorists and intellectuals; the role of government repression in Italy, France, and Spain as the major generator of retaliatory political violence; a comparative discussion of violence as perpetrated by Spanish, French, and Italian anarchists; and the experiences of Italian migrant laborers at home and abroad.

The authors manage to address all of these topics in under 200 pages, excluding the bibliography and index, and in accessible and vivid prose, no more so than in the biographical portraits of the six Italians who carried out assassination attempts.

In the Anglo-Saxon world, such political violence often was attributed to innate Italian tendencies. But Italian social scientists, most notably Cesare Lombroso, Scipio Sighele, and Enrico Ferri, “frequently reinforced the stereotypical image of Italians as innately violent with ill-considered generalizations of their own.” For Lombroso, anarchists were significantly different from “normal” people; they suffered from hereditary defects and their ideology was atavistic, a throwback to “prehistoric society before the rise of institutions of authority.” Anarchists, in other words, were born criminals.

Their violence, however, was not an aberration but rather a tactic they inherited from Italian history, particularly the Risorgimento. Political violence was integral to the struggle for national unification, and anarchists, as inheritors of the tradition, adopted the “same methods of struggle—insurrections, bombings, and assassinations.” Italian anarchism in its formative years was an amalgam of the “revolutionary democracy” of such Risorgimento figures as Carlo Pisacane, Giuseppe Mazzini, and Giuseppe Garibaldi.

Certainly, the state established by the Risorgimento gave workers and peasants reasons to revolt; bad economic policy, including onerous taxation, combined with poor harvests and economic downturns, led to “spontaneous revolts” that “were quelled by the army in a brutal demonstration of how unhesitatingly the new Italian liberal state would use violence against the working classes.” As the authors note, “Government repression and persecution were among the most important precipitants of Italian anarchist violence.” The Italian state’s so-called liberalism, in the “classic nineteenth century sense of the term,” was “enjoyed only by the privileged classes” who had property and high social status. In the decades following national unification, “those who challenged economic and political power were subjected to pervasive violence, with or without the contribution of the anarchists.” Italy, in the nineteenth century, was “a virtual police state for anarchists,” who although never constituting an actual revolutionary threat, experienced the state’s full “arsenal of repressive measures.” Given the severity of state repression, it is remarkable that anarchists “committed so few attentats.”

The chapter “Malfattori: Government Repression and Anarchist Violence” describes the mechanisms of repression: first, define anarchists as criminals, rather than political subversives, and then apply to them measures originally designed to be used against “common criminals”: ammonizione (admonishment or cautioning) and domicilio coatto (internal exile, that is, confinement in prisons, under often atrocious conditions). The effectiveness of these repressive measures had much to do with the fact that they were administrative and not criminal proceedings; there were no trials so the accused could not mount a legal defense. “The individual was entirely at the mercy of the police who provided evidence and had no legal recourse to appeal a condemnation.”

(The penal colonies established for anarchists continued to exist under Fascism and even beyond; the anarchist theoretician and militant Errico Malatesta escaped from confinement on the island of Lampedusa, where today migrants and asylum seekers from Africa and elsewhere are confined in what author Stephanie Malia Hom in her recent book Empire’s Mobius Strip describes as a state of “temporary permanence.”)

Those anarchists who preferred the “propaganda of the deed” to other tactics were known as “anti-organizzatori;” they were “obsessively opposed to all forms of organization.” This opposition, although inextricable from a justified fear of government repression, led to “a fragmented movement of small, unconnected groups” that became “increasingly isolated from the masses and their associations, especially labor unions.” The book’s judgment of them is harsh but accurate: they were “self-marginalized, incapable of collective action, and surpassed in influence” by “legalitarian socialists” who organized and acted openly and often within the parliamentary structure. As the authors note, however, at times the illiberal liberal Italian state also persecuted socialist leaders and parliamentarians.

The book’s mix of narrative and interpretative history particularly shines in its treatment of the figures who carried out attentats. Those who weresuccessful and those who failed. All men, or rather nearly all, came from working-class backgrounds (Angiolillo was the only one of bourgeois origins); none had more than a third-grade education, and all were northern Italians, except for Angiolillo, who was from Puglia. Their violence was motivated by “a complex mix of multiple causes and catalysts,” including class background, poverty, government repression, and the “travails of migration or exile.”

For American, and certainly Italian-American radicals, the chapter on Gaetano Bresci will have particular interest. A silk weaver who emigrated from his native Prato to Paterson, New Jersey, he represents the transnational and diasporic aspects of the anarchist movement. His involvement with the substantial immigrant anarchist community in Paterson “influenced his thinking and commitment to revolutionary action.” After Bresci assassinated Umberto I, Italy enlisted the U.S. federal government in an investigation of U.S.-based anarchists supposedly involved in a plot to kill the king. Paterson was a logical target for police investigation because “it was a major center of radical activity and a nexus for the transnational ebb and flow of prominent anarchist leaders and immigrants.” Bresci, however, acted on his own and not as part of an organized conspiracy. The Italian Consulate General in New York launched an investigation with the assistance of city police officials, including Sergeant Joseph Petrosino. Today, the Italian-born Petrosino is seen as a hero because he was killed in 1909 while in Sicily investigating the Mafia. (Petrosino unwisely went unarmed to a rendezvous in Palermo.) Less known is his antipathy to radicals like Bresci and his fellow anarchists, whom he hated as much as mafiosi.

Bresci’s assassination of Umberto I marked the end of the “so-called heroic period of Italian anarchism,” which opened the door for the movement to become more ideologically complex and militant, a period that lasted until World War I. After Bresci, “the propaganda of the deed” no longer played a role in Italian anarchism.

Assassins Against the Old Order illuminates, with rich detail and acute analysis, an era of Italian radical history that largely has been obscured by stereotypes and misconceptions, as well as by a dearth of research. It honors the life and work of Nunzio Pernicone, and offers heartening proof that anarchists and Marxists indeed can collaborate—at least in writing history.

***

LEAVING THE BURDENED GROUND, Ava C. Cipri, Stranded Oak Press, 2018, 21p

REVIEWED BY DANIELLE MAGGIORE

The poems in Ava C. Cipri’s collection Leaving the Burdened Ground tell a story of growing up with all the trademark themes of a coming of age story — denial, honesty, sexuality, nostalgia, vulnerability, and acceptance, to name a few. They take the reader on an honest journey, despite the fact that the first poem in the collection, “Heidi’s Kaleidoscope,” opens with the line “I can’t be trusted.” Cipri presents a consistent speaker throughout all of the poems, one the reader can’t help but trust due to her matter of fact tone.

Cipri’s poem “Here” does a fantastic job of laying out the various stages of life, from early childhood where “I learn first position” through middle school, high school, and college where “I study rock formations”. Through each step the speaker takes in life, the reader can feel the emotions behind the events while still being kept at a distance through the aforementioned matter of fact tone that Cipri employs. The poem is intimate and impersonal, familiar and foreign all at once, something not easily achieved.

Regardless of the distance between speaker and reader, the poems still present as vulnerable and emotional. A recurring theme in the collection is ballet and it is first introduced in the poem “Nicolinis (Capezio Ballet Pointe Shoes)”. The poem starts off describing these shoes before addressing them directly. The speaker pleads with them “Please don’t let me fall, / … let my bones never brittle, Nicolinis. / … Please don’t let me / get my period; let me stay flat / and never develop breasts, Nicolinis.” In this poem, the shoes become more than shoes — they become a segue from present to a specific future the speaker hopes for. The reader learns in later poems that this is not a future the speaker ever attains, but in this moment, the speaker, pleading with the ballet shoes, brings the reader back to a moment everyone has at some point in their life. A time where they want something so desperately that they would do anything for it and can think of nothing else.

Overall, Leaving the Burdened Ground is a beautifully crafted poetry collection. The poems take the reader on a journey through the speaker’s life, getting intimate while holding the reader at a distance, and clueing the reader in to key moments in the speaker’s life. The poems express a vulnerability while balancing fact with emotion through a brilliantly crafted and consistent tone and clear, strong imagery.

INTERVIEW WITH AVA C. CIPRI

What is your writing process like?

Due to disability, I use audio dictation software, so I approach the page differently. I don’t edit initially and sometimes compose initial drafts in prose. Other times the form and language reveals itself immediately. I am an advocate of letting work sit and coming back to it (hours, days, weeks) later, so I’m always actively writing more than one poem. Also, I keep a running list of things I want to write towards: fascinating news snippets, inspiration from poems/art/science, memories, etc. If nothing actively drives me to write or revise on a given day I make myself write for 10 minutes, timed writing. Most of the time nothing comes from it, but every so often there is something to write towards. If I am struggling to pin something down on the page I write into it to move through the block; that is the most important skill I’ve picked up.

What was your main inspiration for this collection?

Whether from the perspective of childhood, adolescence, or adulthood the narrator in Leaving the Burdened Ground is haunted and burdened in obsessively trying to create/recreate happily ever-afters. The chapbook navigates loss, love and lovers, dance, sexuality and sexual identity, disability, coping mechanisms and addictions, and coming clean.

What poem from this collection are you most proud of and why?

“Female Dragonflies Fake Sudden Death to Avoid Male Advances” for the integration of a scientific article, which spoke to me and many women on social media. For its challenge and risk taking voice in translating its facts through multiple dialogues, narrated experiences, and raising the stakes through momentum and tension in the poem.

What other writers/poets do you love to read?

Both Fatimah Asghar and Ocean Vuong for how they navigate family relationships, displacement and identity, sexuality and sexual identity, and utilize so many forms. Agha Shahid Ali for his beautiful longing, language, and musicality. Franny Choi for everything about her work; I don’t know where to begin. Jan Beatty, Denise Duhamel, Kim Addonizio, and Alexis Rhone Fancher for their razor-edged empowered voices, naming names, and lusty poems. Lauren Russell for her brave voice and innovative forms. Stacy and Sarah Ann Winn for their dreamy retelling of myths/fairy tales and wonderful syntax. Jennifer Gavin and Jessica Cuello for their haunting mythic lyric voices. Jeannine Hall Gailey for her wit-filled pop culture persona poems. Three uncompromising wild chapbooks I’m currently reading from The Atlas Review Press: boy/girl/ghost, by torrin a. greathouse, We Ran Rapturous, by Shannon Sankey, and Darkcutter, by Kina Viola. And always, Lucille Clifton, Elizabeth Bishop and Emily Dickinson, always.

How would you describe yourself as an Italian-American writer?

It’s inseparable from my identity. I spent my childhood years in a predominantly Italian neighborhood from Stanford’s West Side. Although some people might consider food or religion as central influences in their heritage, that wasn’t the case for me. Alright, we did have those weekly Italian Sunday dinners at my grandmother’s house. You see, my father, Mario, was one of eleven children, making for quite an extensive family. And, yes, I was raised as an Italian Catholic, but I was defiant in religion class, asking questions that often got me into trouble. Still, the main influence came from my father’s work as a tree surgeon; a trade passed on to him by his father from Calabria. It’s a job that not only my father held, but my uncles and great uncles, my brothers and sister (at one point), and now my third-generation nephew, Shaun, has his own business. I’ve grown up with a deep appreciation for nature, particularly trees. My father is also an artist, as are a number of his siblings, not to mention my grandmother. Many of my uncles took to carving wood, even totem poles. Art was a necessity; it was inseparable from the work they did.

Finally, is there anything else you’d like to talk about or let our readers know?

I’m finishing my first full-length manuscript years after my MFA! I think there are only two poems from my original manuscript; I had to let go of the old work to find my direction. Also, how Carlow University’s Madwomen in the Attic workshops have been crucial in claiming my space and voice. After years of hiding behind abstract images and cryptic language, I’m embracing the “I” narrative. I have so much deep gratitude for the instructors and the Madwomen I run wild with in Pittsburgh.

LIZZIE, SPEAK, Kailey Tedesco, White Stag Publishing, 2019, 52p, $15

REVIEWED BY DANIELLE MAGGIORE

Kailey Tedesco’s poetry collection Lizzie, Speak is so many contradicting things; it is somehow eerie, brutal, strange, and beautiful all at once. There’s something so compelling about the poetry that even when the subject matter turns to the grotesque and off putting, you want to keep reading because you feel so drawn into the story that Tedesco has created with her words. For example, no one would say that they want to read about “stuffed ghost-heads”, yet who could turn away when they get to the lines “they say / every killer- / girl has a music box / heart: wound up & / spinning, numbering”? The collection definitely reads as a more mature and developed version of the Lizzie Borden nursery rhyme we all heard as children, which was the spark that ignited this whole collection of poetry in the first place.

The unusual spacing of the words on the page in most of the poems are like the forgotten gaps in a story that no one will ever really know the truth about, it’s almost as if Tedesco is using her poetry to lead a seance with the reader, to channel Lizzie herself. The words come from Lizzie, and the gaps between them show a connection between poet and poem that Tedesco has masterfully gained control of. She hasn’t just been led around like a planchette on a ouija board, but rather has pulled meaning from them and crafted a narrative the way one would read tarot cards. Her poetry has become a form of divination in itself, seen throughout the collection, but most notably in the poem “I Ask the Nether World if Lizzie Did It”.

The spirit of Lizzie Borden has truly been captured within Tedesco’s words, and she gives no greater explanation or example of the staying power of this kind of urban legend than when she says in her poem “Lizzie New Age/Lizzie New Wave” that “I’ll go on cobwebbing the walls with my echo”. Some legends just never die, and with a poetry collection like this written about her, Tedesco has ensured that Lizzie will certainly be one of the ones that lives on.

INTERVIEW WITH KAILEY TEDESCO

What is your writing process like?

I’ve always been the type of person who gets extremely fascinated by one specific thing, and then I feel as though I need to know as much as I possibly can about whatever that one thing is as quickly as possible. This is usually the impetus for all of my writing — something sparks my interest and then three days later I’m in a 25-tabs-open-at-once internet hole with my cursor flashing over a draft of a poem.

I also practice automatic and trance writing techniques. I love automatic writing & free-associating! I wrote more about this process for Luna Luna Magazine: http://www.lunalunamagazine.com/blog/trance-writing-using-the-self-as-a-guide.

What was your main inspiration for Lizzie, Speak, aside from Lizzie Borden of course?

I had just finished my first collection, She Used to be on a Milk Carton (April Gloaming Publishing), which was my MFA thesis and also a kind of heavy deep dive into my own childhood. After completing this, I knew I wanted to get out of my own head for a while, so I started to experimenting more with persona writing and different forms. I’ve always been super interested in Spiritualism and seances, so I thought it would be interesting to write from the perspective of Lizzie Borden as though I was actually channeling her through me. And, I actually did try to communicate with her in several different ways. Weirdly, the most fruitful was using text predictive on my phone, which I sort of see as a more modernized form of a traditional seance.

I also wanted to confront certain parts of myself that made me afraid. I often experience pretty intense sleep paralysis, so I wanted to further explore that sensation. I have multiple sleep paralysis demons, but Lizzie Borden was the most frequent one to appear, especially when I was younger. She always pulled at my ankles to the point where, when I was fully awake, my feet would be hanging off the end of my bed. This image made it into a few poems in the collection.

What poem from this collection are you most proud of and why?

I would have to say the titular poem, “Lizzie, Speak”. In the first draft of the collection, this poem was very different than the one that made it into the book. I felt this huge pressure to make this poem say so many things at once, and for a while, I really struggled to get it where I wanted it to be. During a round of edits, my editor confirmed my fears that it wasn’t necessarily as impactful as it could be. So, I scrapped the whole poem and started over using a more intentional trance writing practice. The result shocked me. I could really feel a conversation between Lizzie Borden and I opening up, and that was exactly the result I had been working for. I felt like I had tapped into something almost alarmingly real in this piece, like I was seeing the images come together through a second set of eyes. There were several moments like that for me while writing this collection.

What interests or hobbies do you have that you find fuel your creativity?

I love horror movies! My husband and I try to watch one new movie a week. When I’m feeling stuck, creatively, I know that certain images and aesthetics from horror films will help to get me going again. Lately, I’m really into abject horror & examining who or what is “cast off” and why.

I’ve also been trying to do more with my hands — baking, crafting, and working with clay. I really like the experience of touching and handling the materials I’m working with. When I’m having a hard day, I make a pie or a quick galette. Touching each piece of fresh fruit individually and then watching it all coagulate and gush under the heat of the oven feels strangely powerful and expressive to me.

What other writers/poets do you love to read?

This is such a hard question because it’s really always evolving! There are so many writers that I admire, so I’ll narrow this to just those that I’m reading and loving currently. Right now, I’m reading Book of Levitations by Jenny Sadre-Orafai & Anne Champion and The Chosen One by Vanessa Maki. I’m so excited to read Witch Doctrine by Annah Browning. I find myself consistently drawn to the work of Sabrina Orah Mark, Jac Jemc, Selah Saterstrom, Carly Joy Miller, and so many more. My classic favorites are Sylvia Plath, V.C. Andrews, Lucie Brock-Broido, and Shirley Jackson. I’m a humongous Shirley Jackson fan, and I hope it shows!

How would you describe yourself as an Italian-American writer?

I grew up knowing very little about my heritage, but I recently got an ancestry.com account for Christmas. I learned that my great-great grandparents owned a little Italian grocery store in Massachusetts. And it’s strange because, on my mom’s side, my great-great-grandmother was Lizzie Borden’s neighbor in Fall River, MA. I didn’t know both sides of my family came from MA, but it’s a place I’ve been drawn to again and again, so it makes perfect sense. This past fall, I read at I AM Books in the North End of Boston with Jennifer Coella-Martelli, Olivia Kate Cerrone, Julia Lisella, Stephanie Laterza, and many more incredible writers. It was one of the warmest readings I’ve ever been a part of — it felt like home.

Finally, is there anything else you’d like to talk about or let our readers know?

My newest collection, FOREVERHAUS, will be out from White Stag Publishing later this year! It’s an exploration of hauntings, in every sense of the word. I’m really excited to share more information about it very soon!

***

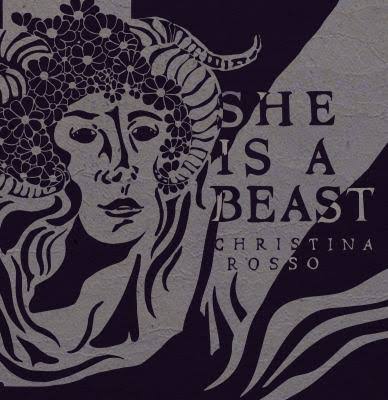

SHE IS A BEAST, Christina Rosso, APEP Publications, 2020, 56p, $18

REVIEWED BY DANIELLE MAGGIORE

Christina Rosso’s debut collection She is a Beast is a series of six fairy tales, each one with a twist. With the surge of fairy tale retellings and reimagining over the past four or five years, it’s easy for such stories to get lost in a wave of similar stories. She is a Beast is not like that. The heroines of these stories, like Rapunzel in “Ecdysis” and the Siren in “The Siren of the Wailing Lake,” aren’t content to just let life happen to them the way most women in fairy tales were. They know what they want out of life and they take it by whatever means necessary, even if that means becoming awful, monstrous — and beastly.

Rosso’s writing has a beautifully timeless quality to it that fits the fairy tale nature of her stories perfectly and almost acts as a juxtaposition to the gruesome tales she tells. This, combined with the stunning illustrations that accompany each piece, make She is a Beast a treasure to read and look at even beyond the compellingly grim and enthralling content of the stories themselves. The prologue may say “This book is for the beasts”, which it certainly is, but I also think anyone who reads this will find something they love about it, whether they are beasts themselves or not.

INTERIVEW WITH CHRISTINA ROSSO

What is your writing process like?

My writing process is usually pretty relaxed. In most aspects of my life, I have set schedules and lists; I love order. But I’m the opposite when it comes to my writing. Too much preparation or organization hinders my creativity. So, I usually start with an idea, a conversation, or an image of a scene and go from there. I often don’t have many aspects of the story figured out before I sit down. Sometimes, that can be frustrating, however, usually, I find it freeing and exciting to see where the story winds up. I like to let the characters and the story follow their own course.

I try to do a lot of my writing at my desk, which also seconds as an altar. I have a mantra I say to myself before I begin and light a candle I’ve dressed to inspire prosperity in ideas, writing, and acceptances. While the candle is going, I write, edit, or submit. I blow it out when I’m done for the day. I’ve found this simple ritual has really helped with my productivity.

I also often write stories, or ideas for them, in my phone’s Notes. If an idea or a sentence comes to me, I don’t want to lose it!

What was your main inspiration for She is a Beast?

My main inspiration for She is a Beast is The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter. I discovered this collection of feminist fairy tales during my graduate program at Arcadia University. Published in 1979, this book opened a whole new world for me of research, imagination, and writing. Carter revealed what she called the “latent content” in these classic tales, with a focus on gender, sexuality, and identity. My work has always dealt with the politics of gender, sexuality, and identity, and The Bloody Chamber showed me how I could do this in a new genre–fairy tales. I don’t know if I would have written this book if it wasn’t for Angela Carter paving the way.

What story from this collection are you most proud of and why?

It’s hard to pick one, but I think the first piece in the collection, “Killing the Beast,” is the story I’m most proud of. I started writing it about two-and-a-half years ago and couldn’t quite figure out how to write the ending. I knew what happened, but I didn’t know how to get there, if that makes sense. When I decided I was going to put these six stories together into a collection, it pushed me to hunker down with this particular story and I’m really proud of how it turned out. It re-imagines one of my favorite fairy tales, Beauty and the Beast, with a character at its center who will do anything to gain her freedom. She won’t end up with Mayor Greyson (the Gaston equivalent) or the Beast. She’ll be no one’s bride, and that to me feels like a better ending for a character as strong and intelligent as she.

What interests or hobbies do you have that you find fuel your creativity?

I own and run an independent bookstore in South Philadelphia, so I’m constantly reading. I’ve always found that reading inspires my writing, whether it be the type of stories or the style.

I also find that any activity that gives my mind time to wander is great for creativity, such as yoga, walking my dog, Atticus, or acupuncture.

What other writers do you love to read?

When it comes to feminist fairy tales, I love to read Angela Carter, Emma Donoghue, Daniel Mallory Ortberg, and Nikita Gill.

I also have recently gotten into mystery novels, such as the Claire DeWitt series by Sara Gran and The 71/2 Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle by Stuart Turton.

Some of my favorite local or small press writers are Cathy Ulrich, Madeline Anthes, K.B. Carle, Nicholas Perilli, and Lindsay Lusby. I definitely suggest checking out Cathy’s book Ghosts of You and Lindsay’s book Catechesis: A Postpastoral. Maddie has a book forthcoming from Bone & Ink Press, which I know will be fantastic, too!

How would you describe yourself as an Italian-American writer?

I’m most often reminded of my Italian-American heritage at readings when the host mispronounces my maiden name: Rosso. This has been a common occurrence my entire life, yet it never ceases to amaze or frustrate me. It’s ironic, too, actually that since I got married, no one has trouble saying or spelling my additional last name (I hyphenated): Schneider. It was very important to me to keep my maiden name and to continue to publish under Christina Rosso. I am very proud of the Italian side of my family, a mix of educators and entrepreneurs, all of which are or were the most hardworking people you’ll ever meet. It’s something I have always prided myself on and have always worked towards. I hope to make the Rosso name and its legacy proud.

In your opinion, what is the best part about running your bookstore, A Novel Idea?

The best part about running A Novel Idea is working side by side with my husband, Alex. Also, being able to support local artists, artisans, and educators. I really love that the bookstore has become a center for the community.

Finally, is there anything else you’d like to talk about or let our readers know?

In times like these, it’s important now more than ever to practice compassion and support one another, especially small businesses and artists. I want to give a shoutout to my amazing publisher and illustrator, Jeremy Gaulke, at APEP Publications. It has been a dream to collaborate on this collection together and to see my vision for this book come to life.

Also, Alex and I would be eternally grateful if you would help promote A Novel Idea on Passyunk during this time. Due to COVID-19, we are currently closed. Anything helps, whether it’s sharing or liking our posts, buying gift cards, pre-ordering She is a Beast, or ordering books online via bookshop.org/shop/anovelideaphilly. Thank you so much!

***