Dear Justice by Jennifer Martelli. Grey Book Press. $7

Reviewed by Rina Palumbo

Dear Justice by Jennifer Martelli is a stunning and powerful poetry collection that demonstrates the power of words to shape personal experience within the simultaneously intimate and vast American landscape.

It begins, fittingly, with a letter to an unknown recipient, describing the “scariest scene in The Shining” as the opening one, where a car is driving up to the hotel on a road that “only a helicopter or a bird of prey could follow.” From this aerial scene to the final image of the movie, with Jack Nicholson sitting in front of the snowbound hotel, with “the eyes of a raptor. He’d always been there”, Martelli documents this double journey from high to low, from then to now, organizing the scythe-like sweep of her poetry, making the book as much a map as a kinetic sculpture. Her words exist and shape cusps, allowing us to see and feel the full force of the power and damage the pendulum brings to illuminate and define personal space, public history, and political reality. It is a radical indictment to those set above us wielding authority, with power over us, dictating intrusions unto and into our bodies through their words and actions.

There is a fierce momentum in the following five poems. Her letter to Clarence Thomas starts as a memory of her father, who hated cats and ear piercings and ruled over a household where the loud TV sets in every room “made certain that no one ever spoke to each other.” In this silence, love became an obligation to father, husband, and country. From this silent household into an imagined evening at Thomas’ house, Clarence sits with his wife Ginni in the silence of love as stare decisis, by things decreed. Silence becomes the space filled with cats, earlobes repaired, a quiet status of complicity and domestic routine.

Love as a void filled with prescribed actions is the threshold into spiraling tension that never lets up. And it does not remain silent. Her next poem is written as a letter to an old boyfriend’s disembodied hand, part of a person she once knew and loved, a symbol of force that hits the side of her head, demanding her attention, her ears ringing in alarm. This siren’s wail reverberates into the vastness of memory, jumping up from then and shocking her again. This percussive pulse drives the narrative down and erupts in shards of truth: in the letter to Samuel Alito, frenetically devoting himself to “weighty destruction,” to her mother passing to her daughter a “waking dream of vengeance and atonement” moving and disrupting the material markers of her father in the “Cusp of Cancer”; then a letter Chief Justice John Roberts, describing a ghostly cat, Cosmo, slipping into the “whole night sky/and the very last flower of the fall,” his spectral space marking the completion of the descent to the bottom.

This brings us to the heart of this collection, the zero point before the momentum swings upward. In the poem “To the Zip Tie,” well known as a household object and an instrument of the state. Martelli describes the “nylon toothed-heart of toothed-hearts” as something that binds, gives traction, and can “tame the snakes’ nest of cables and wires.” This is “love” not that which fills the silence but disrupts and chokes, teeth interlocking and ratcheting, tightening and breaking bones until “First I felt adored / then I felt complicit” in the bonds of love, tightening to disrupt the structure of the object now being loved. They are joined in this, stuck at the zero point, contracting and expanding, neither too hot nor too cold, a null space full of fragile yet lethal tensions.

This forcible pulling apart and forcing together brilliantly sets up the rising action of the following pieces. Beginning with “Dear Neal Gorsuch,” which she treats deftly as a discussion of “Ode to Billie Joe,” a song that had “lots and lots of apostrophes: balin’, pickin’, nothin’–a song full of little barbs, hooks that scrape things away.” In the movie version with Robbie Benson, Billie jumps from the bridge. He made love to a man because he wanted to. He wanted to. The morning after, Billie Joe’s shame was unbearable. It is the weight of shame shared by gay, trans, and pregnant people, the moral judgment of others that created this circumstance, and this pressure to be one way. “Neil, what if we didn’t have to be sad about any of this?” Maeteli asks. What if Justice Gorsuch’s weight of judgment was gone? Then, the alternative emerges dimly; “What if we all could sit up high, “droppin’ hellebore; mugwort, thistle, blazin’ stars” into the deep below? Disassociation, the toothed barbs, ripping away the weight of moral judgment, begins these poems’ sharper, higher frequency.

The poem for Christine Blazey Ford has its beautiful, aching underlift, a story told by a young girl. It is a memory, fragments of the moment on a day when, jumping out of the car before the stoplight turned green to mail a letter, she encounters a dog wandering the street, a dog, like all dogs, “with no leashes, and they/ could leave their yards and doghouses at will.” An innocent time, a simple task, and then ” I remember its front paws looked on my/ thigh tight, /choke hold. I remember the dog hanging on. Its nails. I remember someone/ laughed.” The claws digging into her thigh, the sound of laughter. It is this moment, the laughter that whips the poem into immediate counter-response, the anger of her mother calling her back to the car, “I might have imagined/ but not my shame and her arms curved like thick iron hooks.”Again, claws take hold, laughter erupts, and finally, her mother holds her with iron hooks.

This poem, toothed like a zip tie, locks into her following poem, “Dear Brett Kavanaugh,” developing a parallel structure, describing a seahorse, a “hippocampus,” which is also the name of the part of the brain that is the seat of memory. On the cusp of the overturn of Roe v Wade, Kavanaugh’s remembered laughter, now indelible in the hippocampus, is rising into the vast expanse, joining forever the personal and the political, tearing apart with jagged teeth that constrict and rupture the very bones of the people it cages.

Roe v Wade, the decision that permanently altered the power dynamic in this vast land, is quietly retold in Martelli’s letter to Jinx Allen, a figure in a black and white photograph. A famous photograph of a young American woman surrounded by Italian men, like a curve of a tarot reading, all of them trying to determine her fate, trapping her in the frame she must walk away from.

This momentum of upward lift, of stepping outside of predetermined framing, accelerates into power from the cusp of Virgo, into a letter to Amy Comey Barrett, and finally back to the anonymous recipient of the first letter as well. We are here again, poised on the precipice, seeing all the power and danger that these strokes of fate yield.

I began this review before the presidential election of 2024. Reading this important work now, gives it more urgency. This is all of us now, suspended and tense, wondering when the successive acts of violence, like birds of prey from above, will shatter status and send the pendulum once again swinging with sharp and lethal power. Those dead-eyed figures litter the landscape, the predators

always there and waiting, and we are caught in the peril of this landscape. This is an urgent, meaningful, timely work of brilliant insight by an important writer.

***

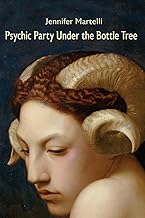

Psychic Party Under the Bottle Tree by Jennifer Martelli, Lily Poetry Review Books, $16

Reviewed by Linda Lamenza

In her latest collection, Psychic Party Under the Bottle Tree, Jennifer Martelli’s poems of strength and resistance give the reader hope. Martelli invites us into her universe in three sections,

each beginning with a quote from a living female poet. Her poems are intense reflections on topics from addiction to vegetarianism, from atheism to the uterus. Martelli has long written on women in politics and women’s rights. She shares with the reader, as one would with close friends, her inner fears: snakes, suffocation, religion, milk gone bad. “But mostly I don’t want to be disregarded,” she laments.

“I remember the day I stopped believing in God,” Martelli says in the first line of “The Memory Floor.” The speaker muses, “Life is scary and we scare so easily. Who would design it this way?” as she faces the impending death of her father and the loss of her mother to dementia. Through Martelli’s precise imagery in the title poem, you will hear the birds’ beaks as they tap the glass bottles dangling from the tree. The speaker asks, “Will we sleep? /Ever at all? Without nightmares or dreams?” A question many of us are asking ourselves in 2025.

Martelli has a way of making ordinary times into the extraordinary. After an elementary school vision screening, the poet wonders, “What would my teacher mark in her green book?” and we see the pure vulnerability that makes Martelli’s work both raw and beautiful. An addicted friend, prior to his death, asks the poet to hold onto his electric griddle. When his ex-girlfriend asks for it back, the speaker tells her she gave it to “someone who needed it,” leaving the reader to reflect on the tradition and meaning of saving the belongings of deceased friends and family.

On the cover, the image is Jean-Léon Gérôme’s painting, “La Bacchante,” a reminder of the speaker’s addiction and recovery journey, as well as the necessary celebrations in life. The bacchantes are female followers of the Roman god Bacchus. (In Greek mythology, he is Dionysus.) They are gods of wine, revelry, agriculture and fertility. These female revelers are pictured with horns on their heads. In addition to the image of the horns on the cover, Martelli references sprouting horns in her poems, as well, as in the form of the Italian horn pendant, a symbol of good luck and protection or alternately, a symbol of the occult.

In today’s complex political and social landscape, when you find yourself in need of some nourishment, pick up this book as soon as possible and cozy up. You will feel like you’ve been invited over for coffee with a good friend, a perfect balm for a cold, winter day.